Watch this on Rumble: https://rumble.com/v6h3vtp-military-memetica-and-digital-warfare.html

What is military memetica? Influencing beliefs in a scientific way through memes through social media. Memetic warfare is a modern type of information warfare and psychological warfare involving the propagation of memes on social media. While different, memetic warfare shares similarities with traditional propaganda and misinformation tactics, developing into a more common tool used by government institutions and other groups to influence public opinion. The concept of memetics derives from the book “The Selfish Gene” (1976) by Richard Dawkins, being defined as a non-genetic means of transferring information from one individual to another.

Over time, the term “meme” became commonly understood as an image, text, video or other transferrable form of digital information, typically spread for the purpose of humor. In Evolutionary Psychology, Memes and the Origin of War (2006), Keith Henson defined memes as “replicating information patterns: ways to do things, learned elements of culture, beliefs or ideas.” Memetic warfare has been seriously studied as an important concept with respects to information warfare by NATO’s Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence. Jeff Giesea, writing in NATO’s Stratcom COE Defense Strategic Communications journal, defines memetic warfare as “competition over narrative, ideas, and social control in a social-media battlefield. One might think of it as a subset of ‘information operations’ tailored to social media. Information operations involve the collection and dissemination of information to establish a competitive advantage over an opponent”. According to Jacob Siegel, “Memes appear to function like the IEDs of information warfare. They are natural tools of an insurgency; great for blowing things up, but likely to sabotage the desired effects when handled by the larger actor in an asymmetric conflict.”

The Taiwanese government and Audrey Tang, its Minister of Digital Affairs, announced their intention to install memetic engineering teams in government to respond to disinformation efforts using a “humor over rumor” approach. The stated purpose of this approach is primarily to counter Chinese political warfare efforts and domestic disinformation. If memetics can be established as a scientific discipline, its potential military worth includes applications involving information operations to counter adversarial memes and reduce the number of prospective adversaries while reducing antagonism in the adversary‘s military and civilian culture, i.e., it could have the ability to reduce the probability of war or defeat while increasing the probability of peace or victory.

The Russian Annexation of Crimea, 2014

Evidence of memetic warfare and other applications of cyber-attacks aiding Russia in their efforts to annex Crimea has been made apparent by reports of roughly 19 million dollars being spent to fund “troll farms” and bot accounts by the Russian government. The intention of this campaign was to spread pro-Russian sentiment on social media platforms, particularly targeting the ethnically Russian populations living within Crimea. This event is widely considered to be Russia’s proof of concept for modern information warfare, and serves as a template for future instances of memetic warfare.

United States presidential election, 2016

Memetic warfare on the part of 4chan and r/The_Donald sub-reddit is widely credited with assisting Donald Trump in winning the election in an event they call ‘The Great Meme War’. According to Ben Schreckinger, “a group of anonymous keyboard commandos conquered the internet for Donald Trump—and plans to deliver Europe to the far right.”

In a 2018 study, a team that analyzed a 160M image dataset discovered that the 4chan message board /pol/ and sub-reddit r/The_Donald were particularly effective at spreading memes. They found that /pol/ substantially influenced the meme ecosystem by posting a large number of memes, while r/The_Donald was the most efficient community in pushing memes to both fringe and mainstream web communities.

Memetics: A Growth Industry in US Military operations was published in 2005 by Michael Prosser, now a Lieutenant Colonel in the Marine Corps. He proposed the creation of a ‘Meme Warfare Center’. In a document on dtic.mil, Michael B. Prosser wrote his Master’s Thesis on Meme Warfare. It reads: Tomorrow’s US military must approach warfighting with an alternate mindset that is prepared to leverage all elements of national power to influence the ideological spheres of future enemies by engaging them with alternate means–memes–to gain advantage. Defining memes. Memes are “units of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation,” and as ideas become means to attack ideologies. Meme-warfare enters into the hotly contested battlefields inside the minds of our enemies and particularly inside the minds of the undecided. Formations charged with Information Operations (IO) Psychological Operations (PsyOps), and Strategic Communications (SC) provide an existing construct for memes and the study of memes, memetics, to grow and mature into an accepted doctrinal discipline. Epidemiology of insurgency ideology.

Using the analogy that ideologies possess the same theoretical characteristics as a disease (particularly as complex adaptive systems), then a similar method and routine can/should be applied to combating them. Memes can and should be used like medicine to inoculate the enemy and generate popular support. Private sector meme application. 3M Corporation employed an innovation meme designed to cultivate an employee culture, which accepts and embraces innovation in product development. As a practical matter, 3M executives endorsed and employed the lead user process in new product development, which translated into a thirty percent profit increase. The innovation meme was key to 3M’s profit increase. The proposed Meme Warfare Center (MWC). The MWC as a staff organization has the primary mission to advise the Commander on meme generation, transmission, coupled with a detailed analysis on enemy, friendly and noncombatant populations.

Here is a briefing of the thesis “A Growth Industry in US Military Operations”

Memetics in US Military Operations

1. Introduction

- Context: This document, a Master of Operational Studies thesis by Major Michael B. Prosser (USMC, 2006), explores the application of memetics (the study of memes) to military operations, particularly in the context of ideological warfare and counterinsurgency. It argues that traditional kinetic approaches to defeating ideologies are insufficient and that a more sophisticated, non-linear approach using “memes” is needed.

- Core Argument: The central thesis is that the US military must adopt a new mindset that leverages “memes” to influence the ideological spheres of enemies and undecided populations.

- “Tomorrow’s US military must approach warfighting with an alternate mindset that is prepared to leverage all elements of national power to influence the ideological spheres of future enemies by engaging them with alternate means—memes—to gain advantage.”

2. Understanding Memes

- Definition: Memes are defined as “units of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation.” They are essentially ideas or cultural information that are spread and replicated through interpersonal and societal interactions.

- Analogy to Genes: Drawing on Richard Dawkins’ work, the document draws an analogy between genes and memes. Genes are physical units of inheritance, while memes are metaphysical and transmitted through communication, actions, and imitation.

- “Where genes are tangible physical elements physiologically passed down and replicated through procreation, memes are metaphysical, intangible entities, transmitted from mind to mind, either verbally, with actions, music, or by repeated actions and/or imitation.”

- Mechanisms: The spread of memes is discussed. Some argue that the “fittest” memes survive (Darwinian-like process), while others contend that the social, economic, and cognitive nature of the host is more influential in a meme’s transmission and replication.

- Influence: The logical progression is that memes influence ideas, which then form beliefs. These beliefs inform political positions, which then drive emotions and actions and eventually influence behaviors. This means that attacking an ideology should be an assault on its central “ideas.”

3. Military Memes

- Production of Memes: Military operations generate memes, both intentionally and unintentionally. Unintended memes often result in second and third-order effects.

- Transmission: Contact – both direct and indirect – with the enemy, friendly forces, and local populations is critical for meme transmission.

- “In the absence of contact, memes are not transmitted, replicated, or re-transmitted. Without contact the conditions for meme transmission are severed.”

- Current Structures (IO, PsyOps, SC): The paper posits that current structures within the military like Information Operations (IO), Psychological Operations (PsyOps), and Strategic Communications (SC) could provide the framework for memetics to mature as a discipline. However, improvements are needed, as these areas do not explicitly recognize or employ the study of memes.

4. Meme Legitimacy and the Clinical Approach

- Private Sector Applications: Private companies have started using meme management and engineering for internal culture shifts and marketing. 3M Corporation used “innovation memes” to foster creativity in new product development resulting in increased profits.

- Clinical Analogy: Defense think tanks and contractors use an epidemiological approach to analyze the spread of insurgency ideology, treating it like a disease, with memes as the vector.

- “The clinical disease analogy for the spread of memes infers a further metaphorical connection to the development and spread of ideologies.”

- This framework seeks to identify conditions that promote the spread of detrimental ideas and then develop strategies, like inoculation with counter-memes, to combat the spread.

- The Importance of Interdisciplinary Expertise: Successfully applying this approach requires understanding sociology, anthropology, cognitive science, and behavioral game theory.

- “There is a nexus at the crossroads of sociology, anthropology, cognitive science, and behavioral game theory that can help us to intentionally persuade (inoculate) large audiences (or hosts) through subtle or overt contact.”

5. Ideological Warfare & Future Nonlinear War

- Challenges: Ideologies are extremely difficult to defeat kinetically. They are dynamic, generate support for complex reasons, contain intangible and tangible aspects and can incite noncombatants.

- Kinetic Limitations: “Gloves off” attrition-based approaches to counterinsurgency are often counterproductive.

- “…It is considered that a “gloves off” approach to any insurgency problem has a strictly limited role to play in modern COIN [counterinsurgency]. Furthermore, the record of success for attrition in COIN operations is generally a poor one…the result of this approach (normally to the delight of an insurgent) is an escalating and indiscriminate use of military firepower.”

- Nonlinear Nature: The paper stresses that future warfare will be nonlinear, with the need to address complex adaptive systems like ideologies.

- Need for Adaptation: The US Military lacks specific doctrines and strategies for this arena. An acknowledgement of this is a starting point for further developments.

- “The US military does not possess a doctrine or prescription for the contest contained in the nonlinear battle space of an enemy’s mind or even the complex paradigm of the noncombatant.”

- DoD Recognition: The 2003 Information Operations Roadmap acknowledged the need to influence diverse audiences to deter aggression, but the tools and methods to achieve this remain a work in progress.

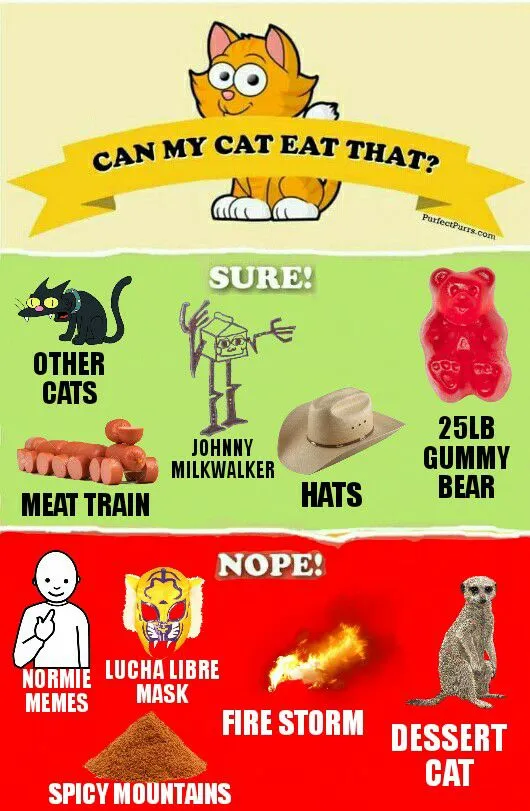

6. The Meme Warfare Center (MWC)

- Proposed Solution: To address the shortcomings, the document proposes creating a Meme Warfare Center (MWC), a staff organization designed to advise commanders on meme generation, transmission, and analysis.

- Structure: The MWC is envisioned as a joint interagency entity led by a “Meme Management Officer” or a “Meme and Information Integration Advisor.” It’s comprised of two distinct centers:

- Internal Meme Center (IMC): Focuses on internal organizational memes, aiming to shape the command climate, culture, and moral of friendly forces.

- Includes experts in HR, psychology, and equal opportunity.

- External Meme Center (EMC): Targets enemy combat forces, noncombatant indigenous populations, and strategic audiences. It’s further broken down into:

- Meme Engineering Cell (MEC): Responsible for meme creation, targeting, and inoculation, staffed with cultural anthropologists, economists, linguists, and other experts.

- Meme Analysis Cell (MAC): Monitors meme feedback, staffed with analysts from social science, behavioral science, game theory, and cognitive science.

- Meme Communications Cell (MCC): Translates memes into acceptable mediums.

- Strategic Communications Cell (SCC): Focuses on global media and technical acumen.

- Key Function: The MWC is designed to conduct combat in the minds of the enemy by strategically designing and deploying memes.

- Superiority to Current IO: The MWC differs from current IO by targeting a broader audience, including noncombatants, and by employing a more robust analytical and interdisciplinary approach.

- “Where current IO doctrinal targeting focuses on enemy forces and formations, the MWC targets a larger more diverse audience. Most significantly, the MWC intentionally targets noncombatants and seeks to provide a nonlinear method of cultivating or supplanting cultural ideas favoring the Joint Force.”

- Addressing JPOTF Weaknesses: Unlike Joint Psychological Operations Task Forces (JPOTFs), the MWC is designed as a permanent organization with a broad spectrum of expertise that can be leveraged for full-spectrum operations.

- “There is insufficient structural and doctrinal background for a JPOTF organization to commence full spectrum nonlinear operations. Personnel are characterized best as ‘part-time executive level help,’ and little intellectual rigor to defend even the most creative and stunning IO campaign.”

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

- Urgency: The paper calls for the US military to test the memetic framework, acknowledging that current operations are conducive testbeds for application.

- Shifting Mindsets: The need for an alternative approach to warfare is a necessity, requiring use of all available national resources to influence the minds of the adversary.

- Interdisciplinary Approach: The paper suggests that success will lean heavily on non-traditional skill sets, including cognitive scientists, cultural anthropologists, behavior scientists, and game theory experts, the new “meme wielding gunfighters.”

- Weaponeering Memes: The US military must actively recognize and “weaponeer” memes to compete in ideological warfare.

- MWC’s Potential: The MWC is presented as a complex, intellectually-rich solution to current doctrinal deficiencies, capable of combating increasingly sophisticated and nonlinear threats.

8. Key Takeaways

- The concept of memes offers a new lens through which to understand and combat ideological warfare.

- Current military structures are insufficient for addressing the complex, non-linear nature of this arena.

- An interdisciplinary approach, incorporating social sciences and behavioral analysis, is essential.

- The MWC, while a conceptual proposal, provides a framework for developing and employing memetic warfare strategies.

- The document serves as an important theoretical approach for the study of information operations, counterinsurgency and the influence operations within the modern battlespace.

This briefing summarizes the key ideas of the document, offering a framework for understanding its argument and potential implications. It emphasizes the need to engage beyond the physical battlefield and address the ideological landscape through the intentional use of memes.

A good article in Medium explains it well. July 14th, 2011. The US Department of Defense put out a press release that went widely unnoticed, buried in a poorly formatted government website. DARPA was forming a new initiative: SMISC, Social Media in Strategic Communications.

At the time, it must have seemed a bit laughable — Instagram had just five million users. The idea of social media “influencers” was nascent. Your parents weren’t on Facebook yet.

And memes still looked like this:

See picture 1

It’s odd, isn’t it? Bad Luck Brian seems like quaint vestigial humor from a different internet. A more structured place, where memes had strict formats enforced by communities like Reddit, imgur, and 4chan.

It was into this primordial memetic environment that the SMISC laid out its four objectives:

1. Detect, classify, measure and track the (a) formation, development and spread of ideas and concepts (memes), and (b) purposeful or deceptive messaging and misinformation.

2. Recognize persuasion campaign structures and influence operations across social media sites and communities.

3. Identify participants and intent, and measure effects of persuasion campaigns.

4. Counter messaging of detected adversary influence operations.”

It’s the fourth point that’s a bit suspicious and smells like propaganda. I’m not making assumptions here; it’s a stated goal. Hold on, because this is where things get a little weird.

Dr. Robert Finkelstein worked on the Military Memetics program, the predecessor of the SMISC. He gave a presentation at the Social Media for Defense Summit a few years back. It’s 155 slides on memes and military applications therein. Putting aside the fact that he calls memes “e-memes” (what a nerd), there are some insidiously transparent goals of the program. For instance, memes will “exploit the psychological vulnerabilities of hostile forces to create fear, confusion, and paralysis, thus undermining their morale and fighting spirit”.

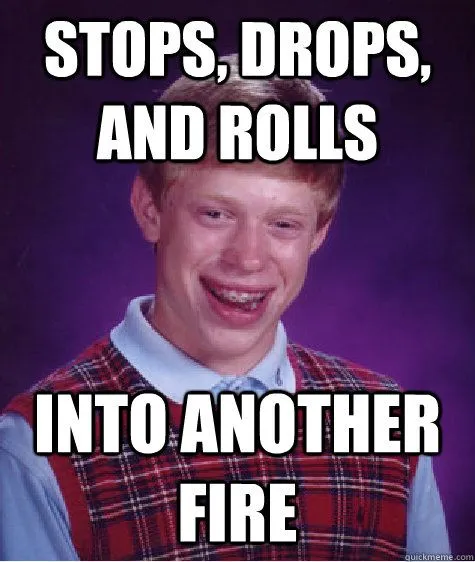

As a matter of fact, Dr. Robert Finkelstein proposed creating an entity called the Meme Control Center as “a framework for meme-war”. This entity would both analyze enemy memes for information and produce friendly memes for offensive purposes.

See picture 2

Whether the Meme Control Center was ever actualized or not is classified information. We’ll never know what happened unless there is some sort of leak (and as of now only the CIA’s very lame internal memes have been leaked).

But simply the fact that this idea was seriously considered at the highest levels of the Department of Defense is remarkable. It speaks volumes about the world we live in and the immense power something as simple as memes can have, whether wielded by 14-year-olds or the CIA.

Keep in mind, it is officially illegal for the US to deploy propaganda on domestic audiences because of the Smith-Mundt Act. However, that hasn’t stopped folks like Dr. Robert Finkelstein from positing that “a post-communism narrative is needed for the global struggle against asymmetric adversaries”.

It also hasn’t stopped the SMISC from partnering with major social media corporations like Facebook to collect user data. And given what we know from the Snowden NSA leaks, one can’t help but be a tad concerned about the ethical quandaries that arise from such research. Especially when a stated purpose of the military memetics program is “Countering terrorists and insurgents before and after they become terrorists and insurgents: influencing beliefs in a scientific way”.

Here’s a list of some of the studies that have been conducted. As odd as it may seem, military researchers take this dead seriously and the program has a massive budget.

– Visual Thinking Algorithms for Visualization of Social Media Memes, Topics, and Communities

-Clustering Memes in Social Media

-From Task to Visualization: Application of a Design Methodology to Meme Visualization

-Two-stage Classification for Tracking Memes in Microblogs

-Competing Memes Propagation on Networks: A Network Science Perspective

But the millions of dollars poured into Military Memetics and the SMISC beg one very, very simple question:

How good can the US government possibly be at making memes?

I’ll come clean about something here: I look at a lot of memes. I consume them voraciously. And I’ve noticed something over the last few years.

In 2011, memes were largely structured with extremely specific rules, like Bad Luck Brian. Posting communities enforced norms and violating a meme format would result in a virtual tar-and-feathering.

However, since that time period, memes have spread across platforms and communities like wildfire (you even see memes on LinkedIn today). Formats loosened and rules became more subjective. Gradually memes were not just canonical images of Philosoraptor and Bachelor Frog, but rather any image overlaid with text. Then they became multimedia — Vine gave birth to audio-visual memes like “My name is Jeff”. Hell, Twitter made memes out of grammar itself- typing without capitalization, purposeful misspellings, and lack of punctuation. Bone apple tea.

Meta-memetics is the modern mode of humor we live in. Memes are often only funny in relation to one’s knowledge of other memes. Formats are invented, played out, and then ironically and humorously inversed, appropriated, or exaggerated. Sometimes in the course of a few days. Bad Luck Brian lasted years. Salt Bae is more transient. Meme trends change so rapidly there’s even a “all of [month] in one meme” meme.

Show picture 3

Taken to the extreme, memes evolve into some crazy Edward Albee/Salvador Dali absurd/surreal anti-humor. Do yourself a favor and spend a little time of the Facebook page “Useless, Unsuccessful, and/or Unpopular Memes”. It is a true subversion of memes: all content submitted must original. And it must be useless. They are anti-memes. An example:

Show picture 4

This sort of anti-meme culture is very closely tied to mental health meme culture, a genre growing extraordinarily fast, cracking self-aware jokes on nihilism, substance abuse, and mental illness to destigmatize and build community. A close friend asked her 15 year old brother what high-schoolers thought was cool these days. He replied, “Wanting to die.” If you think this is concerning, you clearly haven’t been looking at the same memes as me. The 2011 style of memes? Well, they’re now disparagingly referred to as “normie” memes. As Monet was replaced by a signed toilet, so have anti-memes risen. “Ceci n’est pas une meme”. So in this ambiguous, rapidly changing landscape, can the government ever hope to achieve any degree of “virality”? Or is it as hopeless as algorithms producing the next Guernica?

It’s a question that’s more pressing now then ever, especially coming off of the most memed American election in history, with 4chan, Russian trolls, and Bernie Sanders’ Dank Meme Stash occupying hundreds of millions of eyeballs. But it’s a question I can’t answer. By the very nature of the tactic, we can’t see its effect. Russia hired 1,000 trolls. But when you click on, scroll through or get emailed a meme, you can never know who made it. That’s the sublime aspect of memes — no owners, no creators. Just messengers. That’s beautiful, and that’s terrifying.

Memes are also magical. Sigil’s are drawings with demonic attachments. Memes can allow demons access to your home just like opening the front door. You will not find any studies on this because academia frowns on spiritual things. I have written about sigils and how they are used for marketing and sales. We have no proof the military attaches demonic beings to Memetics. Most likely, they don’t need to. Memetics has been so successful that it’s able to control minds and decision making in the subconscious. In example, you see a popular meme that everyone relates to and you feel you are left out of the party. This is shadow shunning and forces you to respond with a lie as if you understood it. Meanwhile, the person looks up the meaning so they can fit in. And even if it goes against their values, continue to be part of the pack.

Now the question I have is, is Military Memetics being used on the American people? The answer is yes.

“We live in an age of disinformation. Private correspondence gets stolen and leaked to the press for malicious effect; political passions are inflamed online in order to drive wedges into existing cracks in liberal democracies; perpetrators sow doubt and deny malicious activity in public, while covertly ramping up behind the scenes.” — Thomas Rid, “Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare”

Since 2016, the digital battlefield has become more sophisticated and widespread across the globe. False information about major events from the Covid-19 outbreak to the 2020 US election is jeopardizing public health and safety. Here we dig into how modern warfare is being waged on the internet, and the steps being taken to stop it.

Since the revelations of Russia spreading false information via social media to interfere in the 2016 US election, the digital battlefield has expanded to include new players and more sophisticated techniques.

2020 has been a breakout year for information warfare, as indicated by the dramatic increase in news mentions of “disinformation” and “misinformation.”

First, the Covid-19 outbreak spawned an infodemic, with false information about virus treatments and conspiracy theories proliferating online.

Then, ahead of the 2020 US presidential election, National Counterintelligence and Security Center director William Evanina warned of nations — including Iran, China, and others — seeking to “use influence measures in social and traditional media in an effort to sway U.S. voters’ preferences and perspectives, to shift U.S. policies, to increase discord and to undermine confidence in our democratic process.”

The stakes are high. Disinformation threatens the globe’s ability to effectively combat a deadly virus and hold free and fair elections. Meanwhile, emerging technologies like artificial intelligence are accelerating the threat — but they also offer hope for scalable solutions that protect the public.

Below, we examine the evolving technologies and tactics behind the spread of disinformation, as well as how it impacts society and the next generation of war.

The state of information warfare: Where are we today?

Though it’s tempting to view disinformation as a modern issue driven by world events and ever-evolving communications technology, it’s important to remember its historical context. Disinformation is not new — it has simply adapted to meet today’s technical and political realities.

“Since the Cold War, propaganda has evolved in a direction opposite to that of most other weapons of war: it has become more diffuse and indiscriminate, not less.” — Joshua Yaffa, the New Yorker

Because the cost and technical skills required for executing an online disinformation campaign are remarkably low, the number of actors and the amount of malicious content have increased.

Further, the threat is not limited to foreign actors — it includes domestic entities as well. In fact, domestic players are expected to have a greater impact on the 2020 US election than foreign actors, according to a report by New York University (NYU).

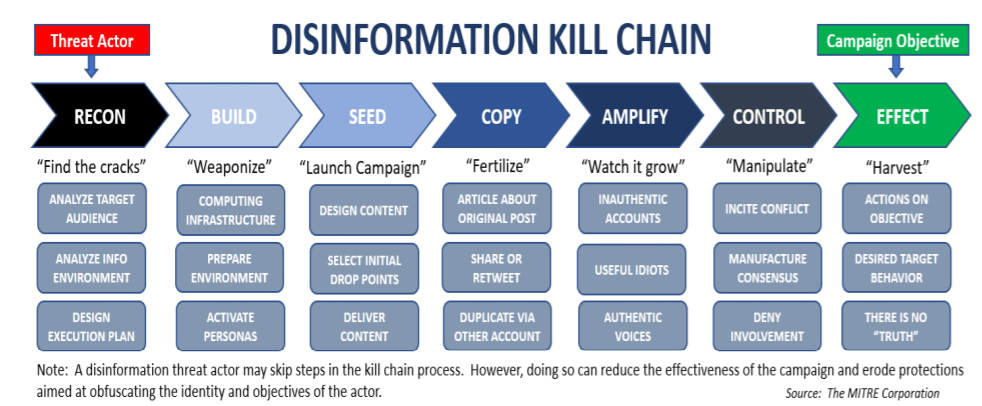

Attackers execute disinformation campaigns using a 7-step process, which the US Department of Homeland Security outlines below:

See image 5

It all begins with an objective, such as generating support for removing sanctions. From there, attackers analyze their target audience’s online behavior, develop online infrastructure (e.g. websites), and distribute manipulative content (e.g. social media posts). To make the narrative more compelling, attackers create supporting information like news articles and amplify the message with computer-controlled accounts or bots.

Over the past few years, this 7-step process has unfolded time and again as nations work to perfect it with new technologies and audiences. Attempts to get the problem of disinformation under control have often fallen flat.

One new technology hampering efforts to combat disinformation is WhatsApp. The communications app encrypts messages to prevent others from reading or monitoring them. The downside of this security is that it creates an environment where disinformation can thrive:

In 2018, false rumors of a roaming group of kidnappers spread on the app, resulting in the killing of more than 24 people in India.

In Brazil, sophisticated disinformation campaigns linking virus vaccination to death spread on WhatsApp and thwarted the government’s efforts to vaccinate citizens against the spread of yellow fever in 2018.

In 2020, Covid-19-related misinformation, from fake cures to false causes (such as 5G technology), spread across the platform.

Seventy countries used online platforms to spread disinformation in 2019 — an increase of 150% from 2017. Most of the efforts focused domestically on suppressing dissenting opinions and disparaging competing political parties. However, several countries — including China, Venezuela, Russia, Iran, and Saudi Arabia — attempted to influence the citizens of foreign countries.

The increase of countries involved in spreading disinformation and of domestically created content coincides with a deluge of false information online. In the case of Covid-19, an April 2020 poll found that nearly two-thirds of Americans saw news about the coronavirus that seemed completely made up.

Most Americans believe that fake news causes confusion about the basic facts of the Covid-19 outbreak. The World Health Organization has spoken about how crucial access to correct information is: “The antidote lies in making sure that science-backed facts and health guidance circulate even faster, and reach people wherever they access information.”

Key elements of the future of digital information warfare

Key tactics include:

- Diplomacy & reputational manipulation: using advanced digital deception technologies to incite unfounded diplomatic or military reactions in an adversary; or falsely impersonate and delegitimize an adversary’s leaders and influencers.

- Automated laser phishing: the hyper-targeted use of malicious AI to mimic trustworthy entities, compelling targets to act in ways they otherwise would not, including by releasing secrets.

- Computational propaganda: exploiting social media, human psychology, rumor, gossip, and algorithms to manipulate public opinion.

1. DIPLOMACY & REPETITIONAL MANIPULATION: FAKING VIDEO AND AUDIO

Correctly timing the release of a controversial video or audio recording could compromise peace talks, blow up trade negotiations, or influence an electoral outcome.

Similarly, malicious actors’ ability to persuasively impersonate world leaders on digital platforms poses a repetitional risk to these individuals. These threats may seem extreme or unlikely, but advances in technology are quickly bringing them closer to reality.

One crucial example is deepfakes, or hyper-realistic doctored images and videos. Deepfakes are a recent development, with news coverage only beginning to pick it up in 2018.

Historically, creating realistic fake images and videos required extensive editing expertise and custom tools. Today, GANs (generative adversarial networks), a type of AI used for unsupervised learning, can automate the process and create increasingly sophisticated fakes.

Much of the code for creating convincing deepfakes is open-source and included in software packages like DeepFaceLab, which is available publicly for anyone to access. This lowers the barriers for adoption, making deepfakes a viable tool for more hackers, whether or not they are tech-savvy.

Unsurprisingly, the number of deepfakes online has exploded over the last few years. According to Sensity, a startup tracking deepfake activity, the number doubles roughly every 6 months.

The vast majority of deepfake videos focus on pornography. However, a small percentage of them have political aims.

For example, a 2018 video of Gabonese president Ali Bongo contributed to an attempted coup by the country’s military. The president’s appearance and the suspicious timing of the video, which was released after several months during which the president was absent receiving medical care, led many to claim it was a deepfake. This perceived act of deception cast further doubt on the president’s health and served as justification for his critics to act against the government.

Another instance occurred in June 2019, when a video depicting sexual acts by the Malaysian minister of economic affairs Azmin Ali created political controversy. In defense, Azmin Ali and his supporters delegitimized the video by calling it a deepfake.

In both cases, analyses of the videos to determine their authenticity were inconclusive — a fairly typical outcome for videos of lesser-known individuals or where only the manipulated version exists.

This uncertainty could give rise to an alarming phenomenon known as the “Liar’s Dividend,” where anyone can feasibly deflect responsibility by declaring an image or video as fake — a tactic aimed at undermining truth. Essentially, the fact that deepfakes exist at all creates an environment vulnerable to manipulation that threatens truth.

Even less sophisticated approaches to video manipulation, known as “shallowfakes” — which speed up, slow down, or otherwise alter a video — represent a threat to diplomacy and reputation.

For example, a shallowfake of the speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi in May 2019 gave the impression that she was drunk and slurring her words. The video, which was retweeted by US president Donald Trump, received more than 2M views in 48 hours.

Whether a deepfake or shallowfake, the accessibility and potential virality of doctored videos threaten public figures’ reputation and governance.

AUTOMATED LASER PHISHING: MALICIOUS AI IMPERSONATING AND MANIPULATING PEOPLE

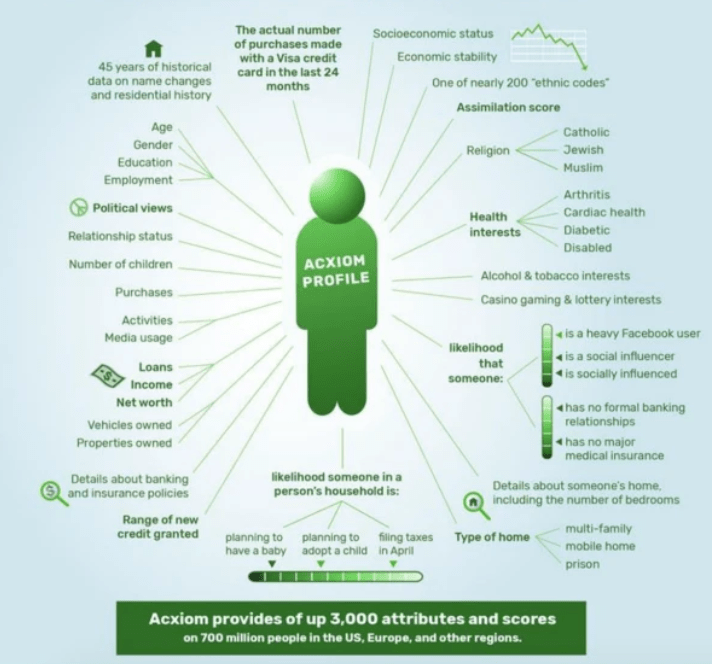

The number of data points available online for any particular person at any given time range from 1,900 to 10,000. This information includes personal health, demographic characteristics, political views, and much more.

See image 6

The users and applications of these personal data points vary. Advertising companies frequently use them to target individuals with personalized ads, while other companies use them to design new products and political campaigns use them to target voters.

Malicious actors also have uses for the information, and owing to frequent data breaches that resulted in the loss of nearly 500M personal records in 2018 alone, it’s often accessible.

Personal data plays a significant role in the early stages of a disinformation campaign. First, malicious actors can use the information to target individuals and groups sympathetic to their message.

Second, hackers may use personal data to craft sophisticated phishing attacks to collect sensitive information or hijack personal accounts.

Population targeting

Targeting audiences, whether through ads or online reconnaissance, is a crucial piece of the disinformation chain.

To exploit tensions within society and sow division, purveyors of disinformation target specific groups with content that supports their existing biases. This increases the likelihood that the content will be shared and that the foreign entity’s goal will be achieved.

Russia’s information warfare embodies this tactic. A congressional report found that the nation targeted race and related issues in its 2016 disinformation campaigns.

While online reconnaissance can identify the social media groups, pages, and forums most hospitable to a divisive or targeted message, buying online ads provides another useful tool for targeting individuals meeting a particular profile.

In the lead-up to the 2020 US presidential election, an unknown entity behind the website “Protect My Vote” purchased hundreds of ads that yielded hundreds of thousands of views on Facebook. Promoting fears of voter mail fraud, these ads targeted older voters in specific swing states that were more likely to be sympathetic to the message. The ads made unsubstantiated claims and, in one instance, misconstrued a quote by basketball star Lebron James.

Personalized phishing

The availability of personal data online also supercharges phishing attacks by enabling greater personalization.

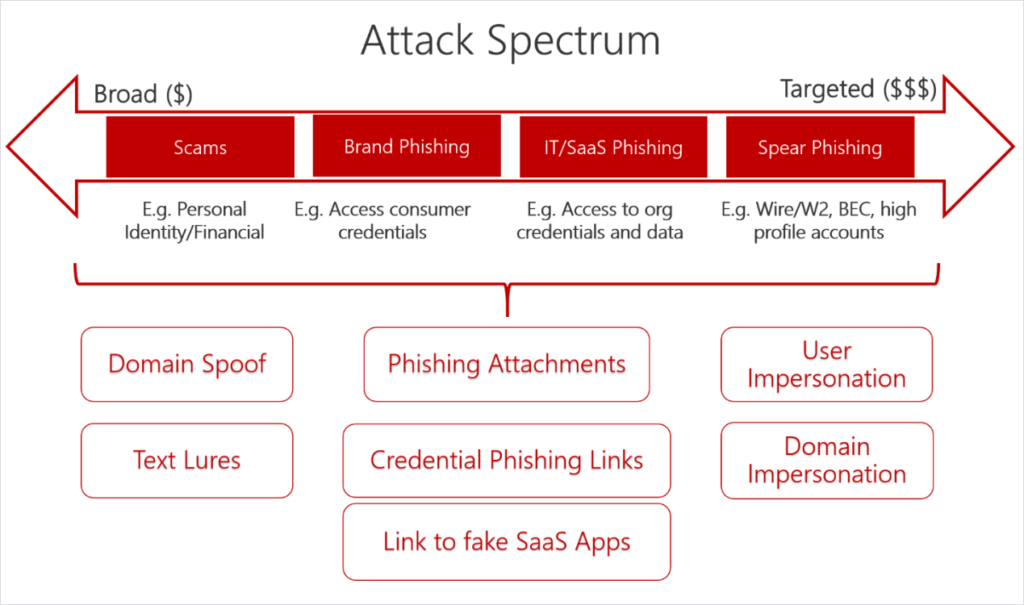

While many phishing attempts are unsophisticated and target thousands of individuals with the hope that just a few take the bait, a portion of hyper-targeted attacks seek large payouts in the form of high-profile accounts and confidential data.

See image 7

If a hacker’s phishing attack successfully steals credentials or installs malware, the victim may face reputational damage. For example, ahead of the 2016 US presidential election, Russian hackers used a spear-phishing campaign to infiltrate Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman John Podesta’s email and release collected information to the public.

Selectively sharing personal or sensitive information provides disinformation campaigns with a sense of authenticity, and leaking the information ahead of significant events increases its impact.

Using phishing attacks to access high-profile individuals’ email or social media accounts also poses a reputational and diplomatic threat. For example, in 2020, hackers gained access to the Twitter accounts of Joe Biden, Elon Musk, and Barack Obama, among others.

This particular incident focused on monetary gain and specifically targeted Twitter audiences. However, it highlights the larger, more dangerous possibility that hackers could impersonate leaders for political ends.

3. COMPUTATIONAL PROPAGANDA: DIGITIZING THE MANIPULATION OF PUBLIC OPINION

Nearly half of the world’s population is active on social media, spending an average of almost 2.5 hours on these platforms per day. Recent polls indicate Americans are more likely to receive political and election news from social media than cable television.

User engagement helps the corporate owners of these platforms — most notably Facebook and Google — generate sizable revenues from advertising.

To drive this engagement, companies employ continually changing algorithms with largely unknown mechanics. High-level details provided by TikTok and Facebook indicate that their algorithms surface the content most likely to appeal to a particular user to the top of their feed.

“So over time, we learn about each person’s kind of preferences and their likelihood to do different kinds of things on the site. It may be that you’re someone who just really loves baby photos, and so you tend to click ‘like’ on every single one. That’s then over time going to lead to us ranking those a little bit higher for you and so you’re seeing more and more of those photos.” — Dan Zigmond, director of analytics at Facebook

Discussion of algorithmic-induced bias in the media has increased over the past 5 years, largely tracking artificial intelligence’s application in products ranging from facial recognition to social media.

The use of algorithms has caused concern about social media perpetuating bias and creating “filter bubbles” — meaning that users develop tunnel vision from engaging predominantly with content and opinions that reinforce their existing beliefs.

Filter bubbles build an environment conducive for disinformation by reducing or blocking out alternative perspectives and conflicting evidence. Under these circumstances, false narratives can exert far more power and influence over their target population.

Because engagement through likes, comments, and shares plays a role in determining content’s visibility, malicious actors use fake accounts, or bots, to increase the reach of disinformation.

At a cost often less than $1 per bot, it’s not surprising that the number of bots on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram totaled approximately 190M in 2017. In August 2020 alone, Facebook used automated tools and human reviewers to remove 507 accounts for coordinated inauthentic behavior.

The vast number of bots on social media platforms is deeply concerning, as bots and algorithms help disinformation spread much faster than the truth. On average, false stories reach 1,500 people 6 times faster than factual ones.

The future of computational propaganda

The technology and tactics used to wage information warfare are evolving at an alarming rate.

Over the past 2 years, the battlefield has swelled to include new governments and domestic organizations hoping to mold public opinion and influence domestic and international affairs.

For example, China expanded its disinformation operations to influence elections in Taiwan, discredit protests in Hong Kong, and deflect responsibility for its role in the outbreak of Covid-19. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan used disinformation tactics to suppress political dissent, with Facebook suspending account activity for a youth wing of the country’s ruling party in October 2020.

Participants in information warfare can easily find the tools to identify cleavages in society, target individuals and groups, develop compelling content, and promote it via bots and strategic placement — all that’s required is access to the internet.

Because of their low cost, even a small chance of success makes these activities worthwhile. Without a significant increase in the cost of participating, information warfare will likely continue on its upward trajectory.

While people are showing more skepticism about content online, they’re also facing increasingly sophisticated fakes. Together, these trends call into question the modern meaning of truth.

In 2016, the term “post-truth” was named “Word of the Year” by the Oxford Dictionary. It was defined as: “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

At this point, it’s generally accepted that we have not entered a post-truth world — malicious actors exert a minor, but still significant, impact on the public’s trust of information. To avoid plunging headlong into a post-truth world, governments and companies must anticipate, prepare, and prevent further abuse of emerging technologies.

source